Ei tässä tarvitse olla Nostradamus sanoakseen luottavaisena, että Lehtosen Kaisa pärjää tänä vuonna. Pärjää jo. Tässä tekstissä tarkoitukseni on purkaa omia ajatuksiani syistä, jotka vievät Kaisan uudelle tasolle tänä vuonna pyöräilyssä:

”Ohjaustanko on pikkaisen alempana. Sitä kautta ajoasento on aika paljon aerodynaamisempi kuin vaikka Havaijilla. Istun hiukan taaempana, jolloin pystyn paremmin käyttämään ajossa pakaroita ja takareisiä” (HS, 31.3.2017)

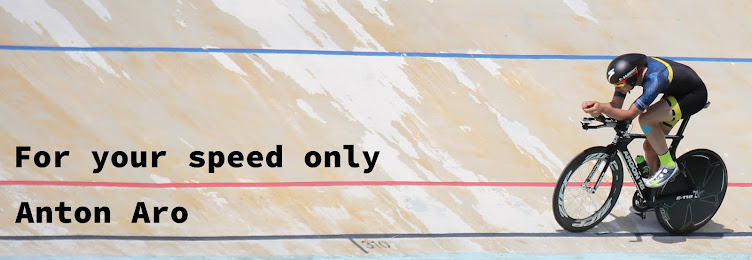

Port Elizabeth 2017

”Pyöritys on nyt taloudellisempaa, kun minulla on näin hirmu lyhyet koivet. Sitten ne lyhyet kammet avaavat vähän lantiokulmaa. Kun edestä on mennyt alas ja satulasta taakse, lonkan koukistajat menevät vähän suppuun. Mutta kun kammet ovat lyhyemmät, kulma aukeaa vähän takaisin päin.” (HS, 31.3.2017)

"Viime vuonna asentoni oli ehkä vähän hassuhko.” (HS, 31.3.2017)

Merkittävin muutos on tapahtunut Kaisan torsokulmassa, joka on pudonnut 8 astetta (22deg → 14 deg). Kun minulla ei ole tehodataa tai muita tarkempia tietoja käytettävissäni käytin kulmiin ja kokoon perustuvaa teoreettista laskentakaavaa (Heil et al., 2001), jossa muutin ainoastaan torsokulmaa ja vastaavaa PWR-SPD-mallinnusta:

2016

|

2017

|

|

CdA

|

0.245

|

0.234

|

Parannus

|

4,55%

|

|

40kmh / teho

|

242W

|

233W

|

Tehosäästö

|

9W

|

Huomioidaan vielä, että Kaisa toteaa myös taloudellisuuden parantuneen, joten voimme olettaa että myös W/CdA suhde on parantunut ja ajo on parantunut silläkin saralla. Lupauksia herättää myös Kaisan ja Ivan O’Gormanin asteittainen lähestymistapa asennonmuutokseen – parempaa lienee siis vielä luvassa.

Asennossa on vielä paljon potentiaalia jäljellä. Visuaalisesti tarkastellen sekä otsapinta-alaan (A) että liukkauteen (Cd) voisi vielä vaikuttaa joa merkittävästi. Kaisa voisi hyvin päästä vielä huomattavasti lähemmäs 0.200 tasoa tai miksi ei jopa alle vaikuttamatta liikaa taloudellisuuteen tai juoksuun. Visuaalisen tarkastelun perusteella (akateeminen jargon-ilmaus joka tarkoittaa: “katsoin valokuvaa”) asun ja kypärän testaaminen toisi parannusta Cd-arvoon. Vaikuttamalla päänasentoon ja asennon kulmiin merkittävät muutokset A:n osalta voisivat realisoitua adaptaatio-jakson jälkeen.

Yhtä kaikki; hyvältä näyttää ja parempaa on luvassa.

Juuri näitä asioita ja muita käsittelemme HelTri:n jäsenillassa Toukokuussa ja pohdimme kuinka jokainen läsnäolija voi parantaa omaa vauhtiaan pyörällä lisäämättä tehoa. Toivottavasti nähdään siellä.